In the report, the Policy Forum notes that the original connection between state revenues and the amount of money the state shares to local governments has been broken, Using some of the surplus to restore a large amount of shared revenues would reverse this trend.Our latest research considers one possible opportunity created by the state's unprecedented projected budget surplus:

— Wisconsin Policy Forum (@WisPolicyForum) February 8, 2022

It presents what could be a generational chance to reimagine the state's partnership with municipalities and counties.https://t.co/84FlP8X1Lg

According to an article on the Wisconsin Historical Society website, municipalities initially received 70% of the state income tax collections, counties 20%, and the state 10%. Over time, not only have the percentages paid to local governments dramatically declined, but the concept of “sharing” state tax revenues as they continue to grow has been abandoned. In the meantime, with the exception of a half-cent local sales tax option granted to counties in the early 1990s and a similar option later granted to a handful of municipal “premier resort areas,” Wisconsin’s local governments have not received permission from the state to levy income or sales taxes. In our 2019 report, Dollars and Sense, we estimated that in 2015, total state aid to municipalities accounted for less than one-sixth of the value of state income taxes. That calculation includes federal aid received by the state and passed along to municipal governments. Moreover, while state income tax collections have more than tripled since the early 1990s, appropriations for the shared revenue program – which is the primary mechanism for upholding the state’s original commitment to redistribute some portion of state income and sales tax collections to local governments – have declined somewhat (see Figure 3). If inflation is taken into account, the disparity becomes more striking. In fact, if the 1990 shared revenue expenditure of $835.6 million had grown at the pace of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), then it would have totaled $1.73 billion in 2021, or more than double the estimated expenditure of $829.6 million.For perspective, giving another $400 million a year in the next 2 years (restoring 1/2 of the inflation-adjusted cuts to shared revenue) wouldn't even cost 1/4 of the projected surplus that we are projected to carry over into 2023. WPF President Rob Henken explained those thoughts some more on the most recent episode of Capital City Sunday with Channel 27's AJ Bayatpour.

Capital City Sunday 2/13/22 Segment 2 https://t.co/qWpLAD9sOV via @WKOW

— JakeEdwards (@JakeMadtown) February 13, 2022

HENKEN: ....Wisconsin is somewhat unique in terms of, Number 1, the exclusivity, the fact that we say to our local governments your only game in town when it comes to the major source of taxation is the property tax. Now, of course there is an exception for counties, there is an option for a half-cent county sales tax, but even that was put in place in the early '90s and hasn't moved upward since that time. But what's happening here [is with] this concept of revenue sharing. So when this system was created back in 1911, when the state created a state income tax, the bargain at that time was is that we are going to reserve the right to use that taxation for ourselves, state government, and local governments, you're not going to be able to tap into that form of taxation, but we the state government are going to make a commitment to share...some portion of the revenues that we earn via our state incokme tax, we're going to redistribute that back to local governments.Henken says that the COVID relief funds that went to local governments should be able to stave some of the strain for the next couple of years, but those are one-time funds to fill in revenue losses and often are targeted for specific needs, and those funds are merely a band-aid that doesn't address the ongoing problem.

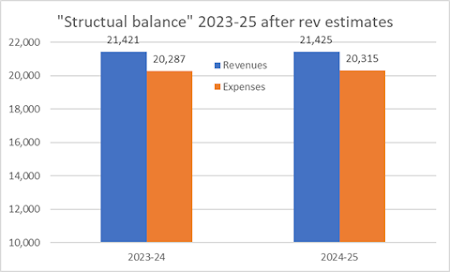

When those [COVID relief] dollars are spent, after 2024 and heading into 2025 budget season, that a lot of these local governments are going to face challenges that exceed the challenges they facing pre-pandemic, before any of this even happened. And where that impact may be most pronounced may be in public safety...We are already seeing some significant stress in the ability of local governments to hire paramedics, to hire part-time rosters of employees in these smaller fire departments to respond to fire and emergency medical service calls.As Henken alludes to, Wisconsin has the fiscal breathing room to be able to put up the funds needed to reform this broken system of funding local governments. Not just with the current $3.8 billion in projected surplus over the next 16 months, but also because of a $1.7 billion "rainy day" fund that literally can't have any more money added to it. And based on the Fiscal Bureau's recent revenue estimates, we have a "structural" surplus of over $1 billion to start the next budget with. In an odd way, the jobs and inflation situation of 2022 works in the favor of the state's budget, because while higher wages and prices translate into more income and sales tax revenue, then budgeted numnbers of many programs are already set, and can't increase without a request from those agencies. And that's if those agencies and programs even need to raise their budgets at all, given the lower poverty rates and need for services. But again, this is all temporary and it means that there will be a need to set aside more funds for these services starting next year. If that doesn't happen, this will result in communities having to decide where those needed services will either have to be (further) cut, or the voters will have to approve more referendums to raise their already-high property taxes. Why should that happen in Wisconsin when we have billions in the bank and an already-high amount of property taxes due to the flawed system that we have? As I've mentioned before, why can't we put together a plan where there's a sizable increase in state aid for schools, where 1/2 of the money goes to replacing and limting property taxes that go into schools, and 1/2 goes into classrooms, teacher salaries, and other K-12 resources. And if you're concerned about local governments being able to maintain police, fire and EMS services, why not allow them to put in a sales tax of 0.5% or 1.0% that is earmarked for those services (we already do a version of this in the 8 small Wisconsin restort towns that have the Premier Resort Tax). We could also change out local wheel taxes for local road aids from the state - or get help via the extra funds that are now available with the sales tax. Now's the time to make these tax changes to adjust to the realities of the 21st Century, and if Tony Evers and Wisconsin Dems want to win in 2022, combining lower property taxes + more funding for schools and cops sure seems like a winning strategy.

No comments:

Post a Comment