Recently, I pointed out that an analysis from “liberal” Yahoo!Finance columnist Rick Newman was misleading readers on the price tag of Medicare for All, as it refused to show the $3 trillion + annual price tag would be mostly offset by lower costs to consumers, businesses and states, making the outcome much less disruptive and expensive than Mr. Centrist wanted to portray it as.

Newman doubled down on the scare tactics with an article from this week titled “The Democratic plan for a 42% national sales tax.” First of all, no Dem has asked for a 42% national sales tax, and few have asked for any type of national sales tax at all. So where is this headline coming from?

Newman uses estimates from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (a front group funded by Pete “Kill Social Security and Medicare” Peterson) to make the claim. After saying Elizabeth Warren’s original 2% wealth tax wouldn’t entirely pay for Medicare for All (no shit, Rick), Newman goes into the ways government could come up with $3 trillion a year for Medicare for All.

Okay, that won’t do it. So what will? CRFB outlined a variety of options. A 42% national sales tax (known as a valued-added tax) would generate about $3 trillion in revenue. But it would destroy the consumer spending that’s the backbone of the U.S. economy. A tax of that magnitude would be like 42% inflation, wrecking consumer budgets and the many companies that depend on them, from Walmart and Amazon to your local car dealer.In addition to the sketchy assumption that all of a national sales tax would be passed ahead to consumers instead of having companies see their profit margins reduced (as we’ve seen with tariffs and other recent add-ons), no one thinks that Medicare for All would be financed entirely this way. It's a pathetic straw man to even bring it up.

Newman adds in a few other scenarios from the Peterson group as a way of coming up with $3 trillion in Medicare for All costs.

Other options include a 32% payroll tax split between employers and workers or a 25% income surtax on everybody. Or, the government could cut 80% of spending on everything but health care, which would include highways, airports and the Pentagon. Or here’s a good one: Just borrow the money and quadruple Washington’s annual deficits.There are a few things Newman doesn't mention that also are part of the equation of Medicare for All. One is that it assumes all costs for services will be the same as today, instead of there being some kind of regulation to prevent everyday procedures from costing big bucks (indeed, Elizabeth Warren's plan assumes those kinds of cost controls).

The best idea might be charging every enrollee in the new program $7,500 per year, so they’d be paying directly for the coverage they’re getting. Some people pay more than that now for health care, by purchasing insurance outright or sacrificing pay raises in exchange for employer coverage. It would still be a nifty trick to propose that to voters.

Another item Newman ignores is that instead of paying higher premiums today, some people currently have no insurance at all and are likely to have their savings drained when some kind of emergency comes on, while hospitals have to make up the difference in uncompensated care. Or that the uninsured are less productive and miss more work because ailments get worse precisely because they don’t want to pay the high price for treatment. But hey, why bring in real life to this analysis when you can just look at dollars and cents?

I want to also go into the source document from the CRFB, where they have a couple of other bits of data that Newman doesn't go into. For example, they provide this chart, which shows who pays a higher percentage of various types of revenue sources that are associated with health care financing.

As you can see there, if you raise federal income taxes to pay for Medicare for All, the richest Americans would pay a lot of the cost. But it's the upper middle-class whose employers pay more money for their health care premiums, while payroll taxes are pretty proportional vs income until you get to the 1%ers. As a side note, this also indicates that scrapping the payroll tax cap that exists for Social Security and/or making up the difference in Medicare tax might be a fair source of funding for a Medicare for All financing proposal.

I also want to mention that the Peterson group adds in a couple of proposals beyond what Newman suggests. First, the $7,500-per-year premium plan could be modified to be more progressive, sliding higher costs toward people who are not already receiving public assistance for their health care.

Require a mandatory public premium averaging $7,500 per capita – the equivalent of $12,000 per individual not otherwise on public insurance. Currently, most Americans are charged health insurance premiums – the majority of which are paid by employers on their behalf. Though current Medicare for All proposals call for ending premiums, policymakers could consider financing Medicare for All through mandatory fixed-dollar payments to the federal government. These payments would be a form of head tax but could resemble premiums in a number of ways. For example, they could vary based on household size and could be paid in part or in whole by employers. They could also be reduced or waived for some individuals, perhaps based on income. In 2021, we estimate those premiums would need to average about $7,500 per capita or $20,000 per household (including single-person households) and is the average applied to all individuals, including retirees, children, and low-income individuals. As an illustrative example, fully exempting everyone who would otherwise be on Medicare, Medicaid, or CHIP would increase the premiums by over 60 percent to more than $12,000 per individual.Not the worst idea, but it loads all of the burden of health care onto the individual while allowing businesses to skate by while getting $886 million in savings from not having to pay for employee health care. Theoretically, businesses would pay higher wages to make up the difference, but why hope for that to trickle down?

I’d have to think any Medicare for All plan would reduce this type of personal premium and make businesses/corporations pay some of that burden. Along those lines, the CRFB gives an example over how a combination of funding methods might work, with the price tag being estimated over a 10 year period.

…Rather than identify a single revenue source to finance Medicare for All, policymakers could combine several options. For example, one could combine a 16 percent employer-side payroll tax with a public premium averaging $3,000 per capita, $5 trillion of taxes on high earners and corporations, and $1 trillion of spending cuts. Other small options, such as a higher excise taxes on alcohol, tobacco, or sugary drinks, could also be included, as could policies to require or encourage state governments to contribute to offsetting the cost of Medicare for All. Adopting smaller versions of several policies may prove more viable than adopting any one policy in full.Warren's plan uses this type of multi-area combination, and that’s likely how any kind of Medicare for All proposal would get through. Remember this passage from the Urban Institute's study of single-payer plans, which points out that a whole lot of businesses, individuals and state and local governments are better off under such a plan since they are already paying for health care today, as their costs are transferred to the federal government.

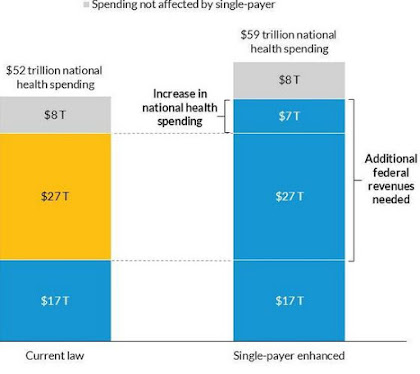

For this approach to reform, federal spending would increase by $34 trillion over 10 years, but health spending by individuals, employers, and state governments would decrease by $27 trillion, so national health spending would increase by $7 trillion over the same 10-year period, from $52 to $59 trillion.Newman ends his article by conceding that Medicare for All could well have better outcomes for a large number of Americans, and be more cost-efficient than the maze that passes for our private health care system of today. But he claims that it would still likely be more trouble than it’s worth.

The $8 trillion includes costs associated with an array of expenses, such as medical care for members of the military and their families while military members are deployed, services provided to foreign visitors, acute care provided to people living in institutions (e.g., prisons and nursing homes), and the value of new construction and equipment put in place by the medical sector. This spending also includes long-term services and supports by states and individuals that would continue under reform. For our purposes here, we refer to this $8 trillion in spending as “spending not affected by single-payer.”

The taller second bar shows that the total national spending under a single-payer program would be higher than under current law. The $17 trillion in federal spending under current law would be shifted to help fund the new program, and the federal government would take over the $27 trillion in current health care spending by employers, households, and state and local governments.

The upside to these impossibly draconian scenarios is that nobody would pay anything for health care, except in the $7,500 example. And it’s possible that Medicare for All would cover health care for more people at a lower total cost than we spend now, meaning the average cost per person would go down. The problem is transitioning from what we have now to whatever Medicare for all would be. And it’s a giant problem, like crossing the Mississippi River without a bridge or a boat. The other side might look great but you’ll die before you get there.But a lot more people will die and/or go bankrupt if we do nothing, Rick. Which should be the point of putting in Medicare for All to prevent that, shouldn’t it? Or are you more concerned with the well-being of health insurance execs and bean-counters over 300 million Americans? The answer Rick and other “centrists” might give to that question would tell a lot.

Bottom line, there are a lot of things we spend big money on and tax for that have much less benefit to society than Medicare for All. And after the reduction in premiums and costs to businesses, whatever small amount has to be paid still seems to be worth it to me. But that's because I'm a nerd who thinks about these things and recognizes there is more to life than my own wallet.

So, one of the arguments against changing our health system is transitioning to another system (like Medicare for all) would just be too hard. What happened to American exceptionalism? It’s a weak, losing argument. My guess is conservatives and the health insurance companies will scare voters with huge dollar amounts.

ReplyDeleteUnfortunately most people confuse health insurance with health care making it easier to sway opinions.

Both points are right on the money. How can the country that sent a man to the Moon 50 YEARS AGO not figure out a way to make health care a human right for its people?

DeleteAnd if health insurance companies have so much money to lie and lobby with, isn't that proof the system is exploitative and in need of major change? I'd say so.

If anyone has a link to what they would consider a comprehensive summary and review of the Canadian Health Care System, I'd sure like to read it. For example, I believe the U.K system is funded by the VAT (unless it just comes from their 'general fund' and isn't 'siloed'), but I know zero about how the Canadians fund theirs, and the degree of co-pays, deductibles, etc. citizens are responsible for, if any.

ReplyDeleteHere's what their government site has. Looks like a lot of funding the province level (equivalent to the state level) with Feds sending block grants to local areas. Not unlike Medicaid in the States, it's run through the provinces.

DeleteThere is also supplemental private insurance that goes on top of whatever the government provides.

Nice to see the parent responding here, and not the bratty 20-something that usually chimes in under that handle.

Very helpful link, thank you. I've just started reading it, but the historical look at it (provided here) is just what I was looking for.

Delete